‘We were there because our country needed us’

By Beth Anne Piehl

Night time can be the toughest for war veterans. Dreams that put them back in the line of fire, amidst unthinkable tragedies and atrocities, are common — even 30, 40, 50 years later.

Night time can be the toughest for war veterans. Dreams that put them back in the line of fire, amidst unthinkable tragedies and atrocities, are common — even 30, 40, 50 years later.

“There’s a saying, that when Vietnam is mentioned, vets will say, ‘Yeah, I was there last night.’ It’s always like you are right back there,” said Craig Smolinski, a Petoskey resident and Vietnam War veteran, whose scars are both visible and intangible.

The lumps of metal under his skin – shrapnel from horrific bombing attacks on his unit in 1969 – remain intact, some 40+ years after his tour in Vietnam, 1968-1969. And the details in his stories remain vivid and gripping, even on a sunny summer day in Northern Michigan far removed from the tragedy and turmoil of war.

Like many other vets, Smolinski said he finds himself grappling with questions, like why did he survive when some 58,000+ United States troops – and many of his close friends – did not. He questions, too, the purpose of the war. And he expresses concern for today’s soldiers – including his son, Benjamin, serving in the Air Force – who are fighting an enemy they can’t always easily identify.

“We were there because our country needed us, asked us, ordered us to go to a faraway foreign land to fight an enemy we knew nothing about,” Smolinski says. “The same thing’s happening today. Young guys and gals are getting killed and for what reason. Why, and for what?”

After graduating from high school in 1967, Smolinski worked on the Great Lakes aboard a limestone freighter, but wanted to take a different career path after experiencing severe storms on the lakes throughout the fall.

In late November 1967, he moved to Petoskey with his mother. Shortly after that, he went to see an Air Force recruiter in Traverse City. But the recruiter told him his quota was full, and Smolinski would have a better chance of joining the Army. At 19 years old, he enlisted.

On March 4, 1968, he was sent to Fort Knox, KY for basic training; next he attended quartermaster school at Fort Lee in Virginia.

The Vietnam War had been ongoing already for about 3 years. “We were all very much aware of what was going on,” said Smolinski, of his fellow enlistees.

The Vietnam War had been ongoing already for about 3 years. “We were all very much aware of what was going on,” said Smolinski, of his fellow enlistees.

After graduating from quartermaster school in July 1968, Smolinski was still not assigned a unit, though he was certain he’d be going to Vietnam. He was right. In August 1968, Smolinski, along with 130 other young men, boarded a 747 in New Jersey bound for Vietnam.

“I’ll never forget walking off the stairway in Vietnam, and the heat is just stifling,” Smolinski recalled. “And it was not only the heat, but the humidity as well was in the high 90s. We filed off in formation and we’re facing a set of bleachers with a tin roof over it. There are 100 or so guys leaving to come home sitting there. As soon as we filed off, the whole group gave us a standing ovation.”

Perhaps because they knew many of the new recruits just arriving in Vietnam wouldn’t make it back home. And their arrival meant a reprieve for the war-weary soldiers waiting to board that 747.

Smolinski soon learned that Vietnam was going to be a 24-hour challenge for body and mind. Sleep came in short spurts on the ground.

“When you first arrive, you’re pretty uptight because most of you don’t know where you’re going,” Smolinski said. “And most of us hadn’t been assigned a unit. That very night we arrived in Saigon, the rockets and mortars started.”

Three days after Smolinski arrived he was assigned to the 9th Infantry Division, 2nd/47th Mechanized (APC’s Armored Personal Carries) Infantry Battalion. The next day Smolinski was flown in a chopper up to Bearcat, which was the old 9th Division base camp.

“That night we got mortared,” he recalled. “I had to run outside of the supply room and dive in a bunker. That was just another awakening of what was to come.”

Two weeks of mandatory jungle training passed and Smolinski and the other newcomers were dropped a few hours from camp into the jungle at night to set up an ambush patrol. Their job was to intercept Viet Cong fighters (North Vietnamese Army) who were moving at night and killing troops. As they walked through a village carrying their c-rations tied up in a pair of boot socks, a young villager boy grabbed for Smolinski food. Smolinski reacted by pulling the young boy into a rubber tree, badly injuring him. His squad leader would not allow him to stop and tend to the injured boy, and that experience still stays with him today. “I don’t know what happened to him,” Smolinski laments.

War time memories come fast for Smolinski, as he shares the events that led to his being awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for bravery.

War time memories come fast for Smolinski, as he shares the events that led to his being awarded the Purple Heart and the Bronze Star for bravery.

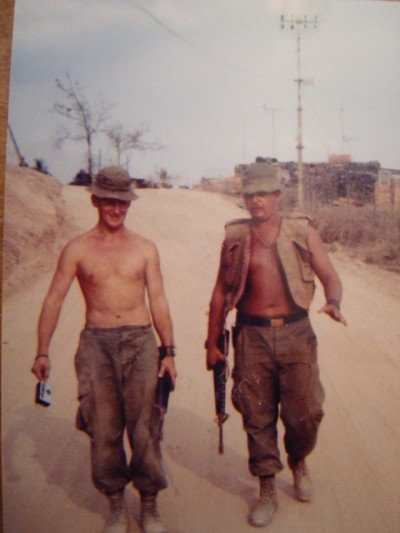

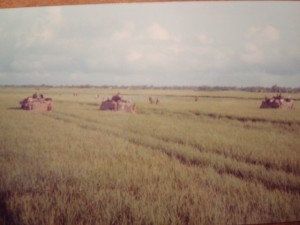

His battalion had been assigned to Binh Phuoc; a base located in the midst of miles of rice paddies 8 miles east of Tan An, south of Saigon. Smolinski’s Company B was assigned to work Tan An area for the month of March 1969. Company B had to line up APC’s along the runways at night.

The Tan An base had medevac choppers and Huey Cobra gunships assigned to the base. It also had a small MASH hospital, barracks and mess hall.

“We would be out all day long, taking different roads, and enemy trails searching for and destroying the enemy,” Smolinski said. “We had to be back at Tan An to pull night security along the runways. My track was positioned near the end of one runway facing the jungle.”

On this fateful night, Smolinski and five soldiers were on watch when small weapons fire erupted from the jungle at 12:30 a.m. Mortars and rockets bombarded the base, one exploding less than 30 feet from Smolinski and his APC. At the same time, his fellow guard Fred W. took an AK47 round to the chest, falling to the ground.

“I immediately jumped down to help him, and a rocket exploded and slammed us both into the side of our track (APC), ” Smolinski recounts. “I had shrapnel sticking into my chest and leg. I pulled Fred to the front of the track, compressing his wound and pushed him under the (vehicle). Tracers and small weapons fire were going on all around us, but I didn’t want to leave Fred there bleeding to death.”

A third soldier with Smolinski was Bobby W. from Texas who was laying out continuous fire from the 50-caliber inside the turret on top of their track. After about 10 minutes he was relieved on the 50-caliber by another soldier from inside the track. He then jumped down and pulled both Smolinski and Fred from under the vehicle, and ran with one under each arm toward safety, dodging bullets and rockets along the way. Bobby was a large man, at least 6 foot 3 weighing 230 pounds. Another rocket exploded behind them and the concussion sent all three in different directions. Smolinski took more shrapnel into the back of his neck.

Bobby, uninjured picked up Smolinski and Fred and somehow kept running. Bobby dumped Smolinski and Fred into the sandbag entry way of the MASH unit. Fred and Smolinski were immediately brought into surgery; both survived their wounds. After Fred recovered, he submitted a request that Smolinski receive the Bronze Star with V device for his heroic actions, which was granted on April 21, 1969, “for heroism in ground combat against a hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam on March 31, 1969.”

Bobby, uninjured picked up Smolinski and Fred and somehow kept running. Bobby dumped Smolinski and Fred into the sandbag entry way of the MASH unit. Fred and Smolinski were immediately brought into surgery; both survived their wounds. After Fred recovered, he submitted a request that Smolinski receive the Bronze Star with V device for his heroic actions, which was granted on April 21, 1969, “for heroism in ground combat against a hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam on March 31, 1969.”

Both men also submitted requests for Bronze Star with V device recognition for Bobby, which was also granted.

The shrapnel injuries proved severe – one ripping through muscle into the calf of his left leg — and Smolinski was unable to return to his Company. He was choppered to the 3rd field hospital in Saigon for more surgery to “patch up” the wounds, then flown in an Air Force Medevac C-141 to Japan for two weeks. From there, he received further treatment at Walter Reed Hospital in Maryland.

For a month afterward, he recovered in Petoskey. Another stint in rehab at Walter Reed followed. His next military assignment brought him to the U.S. Army Vet School south of Chicago, where he worked in supply. The school was set up to teach soldiers to inspect food purchased by the military for US troops in Vietnam.

His official discharge from the Army came in March of 1971.

His official discharge from the Army came in March of 1971.

Today, Smolinski, 63, works with other area veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) and tries to help as many as he can.

“I try to steer as many vets as I can to the (Emmet County) Veterans Affairs office,” Smolinski said.

After his discharge from the US Army, Smolinski worked at Penn Dixie cement plant in Petoskey for nine years. After the plant closed in 1980 he was employed at the Petoskey Post Office until his retirement with 25 years of service.

Never far from his mind is his son, Benjamin. Benjamin has been in the Air Force for five years, and was recently promoted to Staff Sergeant. He is an Aerospace Ground Equipment Technician currently stationed at U.S. Army Garrison Livorno (Camp Darby) in Livorno City, Italy, where he lives with his wife, Amanda.

Son Benjamin Smolinski, USAF

Benjamin Smolinski has directly supported Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Operation Odyssey Dawn and Operation Unified Protector.

And he is immensely proud of his father’s service to the United States of America.

“I am very proud of him and always will be,” said Benjamin, in an email from Italy. “His service is what inspired me to join the military, nearly five years ago now.”

Smolinski’s family

Wife Harriett, married 38 years

Son Benjamin, 29, USAF

Daughter Beth 24, dairy manager at Snow Aisle Food Coop in Everett, Washington

Haley, 33, Gaylord certified pharmacy technician