“My orders were to go to San Mateo and to report on Jan. 15, 1945,” Moose wrote. “My departure for WWII has one image fixed in my mind, that of my mother crying as she and father saw me off to war at the LaSalle Street railroad station.”

By Tamara Stevens

Maurice “Moose” F. Dunne turned 18 on Nov. 30, 1944. Four days later he enlisted in the U.S. Merchant Marine. Four months later he was in the South Pacific serving his country on a bulk vessel cargo carrier named Cape John, a C-2 design freighter that was 459 feet long.

“I lived because the torpedo missed,” Moose said, recalling the time a torpedo nearly hit his ship.

“Bulk cargo ships carried 55 gallon drums of gasoline, kerosene and acetylene,” Moose said. “In essence, the ships were floating bombs. Our ships were used to carry munitions during World War II.”

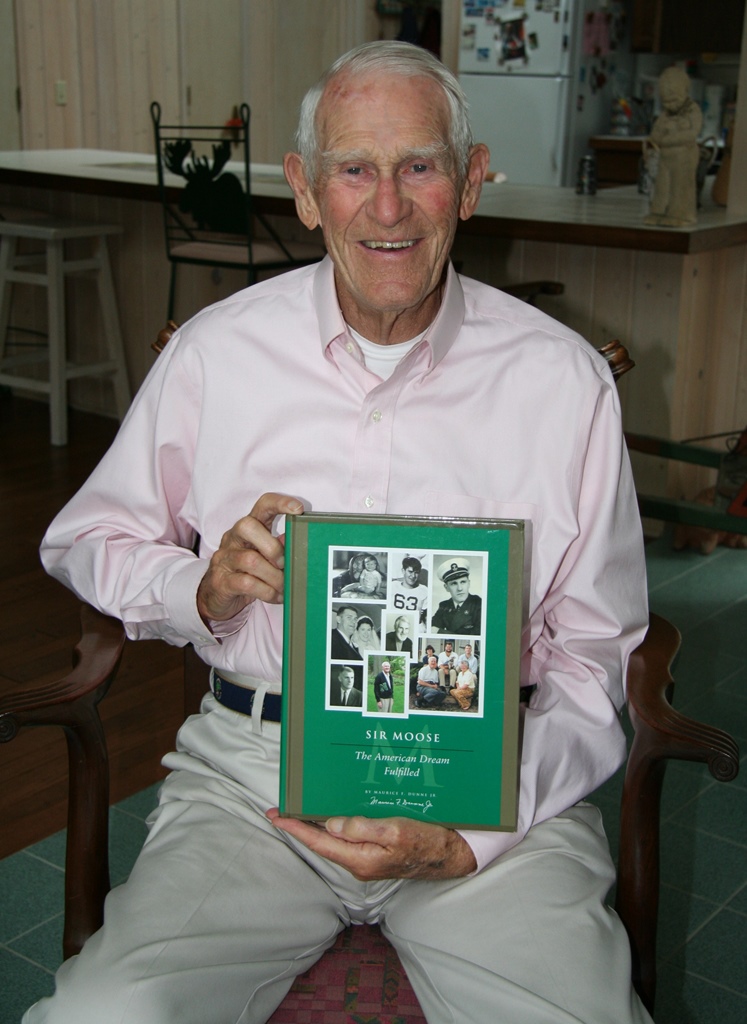

Having the torpedo miss his ship was an incredible stroke of luck, and one that didn’t go unrecognized by the tall man everyone calls “Moose.” Throughout his 90-year life there have been numerous lucky breaks, interesting twists and coincidental connections; so many, in fact, that at the urgings of several friends, Moose penned a book 10 years ago, to commemorate his 80th birthday, chronicling his life.

Sir Moose: The American Dream Fulfilled is a detailed account of not only his life, but also his family’s heritage (his grandfather was mayor of Chicago before being elected Governor of Illinois, but more on that later). The book is an interesting read with countless photographs and memorabilia. An entire chapter describes Moose’s WWII experiences and is narrated directly by him. This article is a combination of our face-to-face interview and quotes from Moose’s book.

Why did the young man from Chicago join the Merchant Marine, the smallest branch of the armed services? Even smaller than the Coast Guard, the Merchant Marine had only 215,000 members, and yet had the highest rate of fatalities of any branch; 83,000 died in service, Moose wrote.

The answer is multi-faceted.

Having graduated from high school in Winnetka, north of Chicago, at the age of 17, Moose had completed a year-and-a-half of college study at MIT and the University of Michigan before turning 18.

“The war I was entering had been going on since I sat in the auditorium of New Trier High School and heard President Roosevelt historical speech, ‘Dec. 7, 1941, a date which will live in infamy….’ to the nation (on the radio) on December 8, 1941,” Moose recalls.

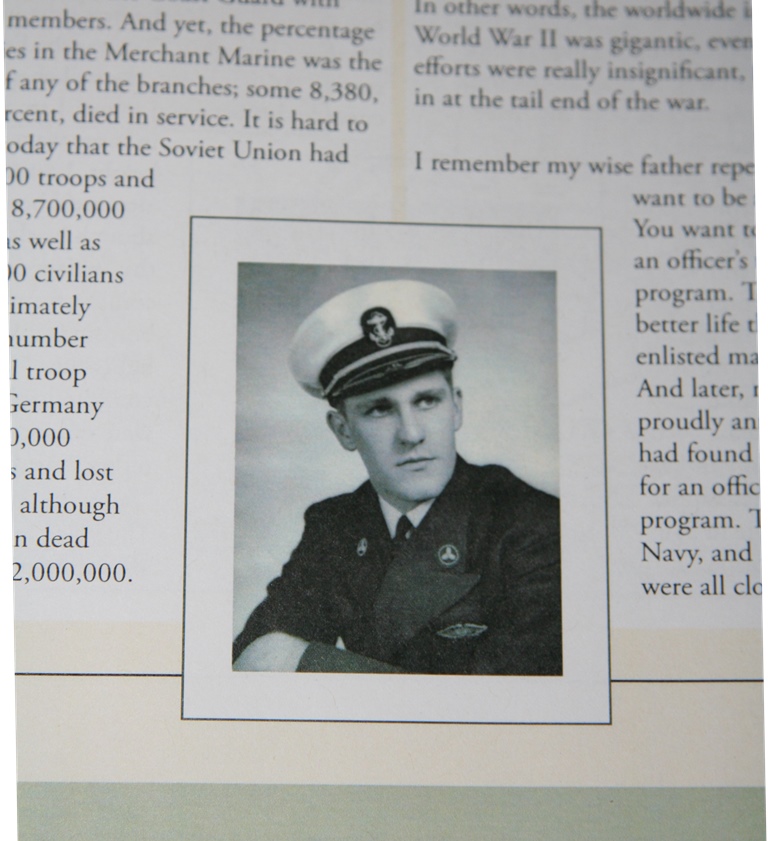

By the time he turned 18, Moose was entering the war at the tail end of it. He remembers his father repeating, “You want to be an officer. You want to get into an officer’s training program. That’s a better life than an enlisted man has.”

Later, his father proudly announced he had found one opening for an officer’s training program. The Army, Navy and Marines were all closed because they didn’t need to train any more officers in the winter of 1944. There was no Air Force as we know it today; in WWII, it was then known as the Army Air Corps.

Moose’s father had found that the Merchant Marine Academy had an opening and spoke with Moose about it. He remembers asking his father, “What’s the Merchant Marine?”

His father explained: “It’s a military service with an academy like West Point or Annapolis, and one reason you’re going is you’ll be double-tracked. When you graduate, you will get either a third mate or a third engineer’s certificate or a commission as an ensign in the Navy, because you are in the Naval Reserve the entire time you are in the Merchant Marine. You’ll choose the Navy.”

Moose naturally obeyed his father, applied, and was accepted.

“I was not only ‘going to war,’ but was also enrolling in a college once again, for my education would continue under the auspices of the Merchant Marine,” said Moose.

About the Merchant Marines

Merchant Marines manned all the ships carrying supplies across both the Atlantic and Pacific, he wrote. The headquarters for the Merchant Marine Academy was then Kings Point, Long Island, New York. Two other academies were established to meet wartime demand; one in Pass Christian, Mississippi, and another in San Mateo, California.

“My orders were to go to San Mateo and to report on Jan. 15, 1945,” Moose wrote. “My departure for WWII has one image fixed in my mind, that of my mother crying as she and father saw me off to war at the LaSalle Street railroad station.”

At the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy, he wrote, cadets went to school for their freshman year to take a survey of everything necessary to learn, and then in their sophomore year they went to sea. Cadets came back to the States for their junior and senior years. In wartime, the freshman year was very compressed, and ran for only four-and-one-half months before being sent to sea.

“The curriculum was not very broad,” he said. “It was steam engineering, electrical engineering, machine shop, ship construction, mathematics, and engineering. We marched in uniform everywhere. Holy shmoly!”

Moose admits to having been only a middling student in high school and at MIT, but in the Merchant Marine Academy he was number one in his class. For the first time in his life he thought, “Gee, maybe I’m smart.” After he’d been in the academy about a week, the cadet below him in the bunk bed asked him if he could help him understand the class work. The next night after dinner they went to a common room in the barracks and there were five or six other classmates there waiting.

“I spent the next two hours answering questions about what we had learned that day,” Moose recalls. “And every night thereafter I became the section tutor. I found that it was kind of fun teaching.”

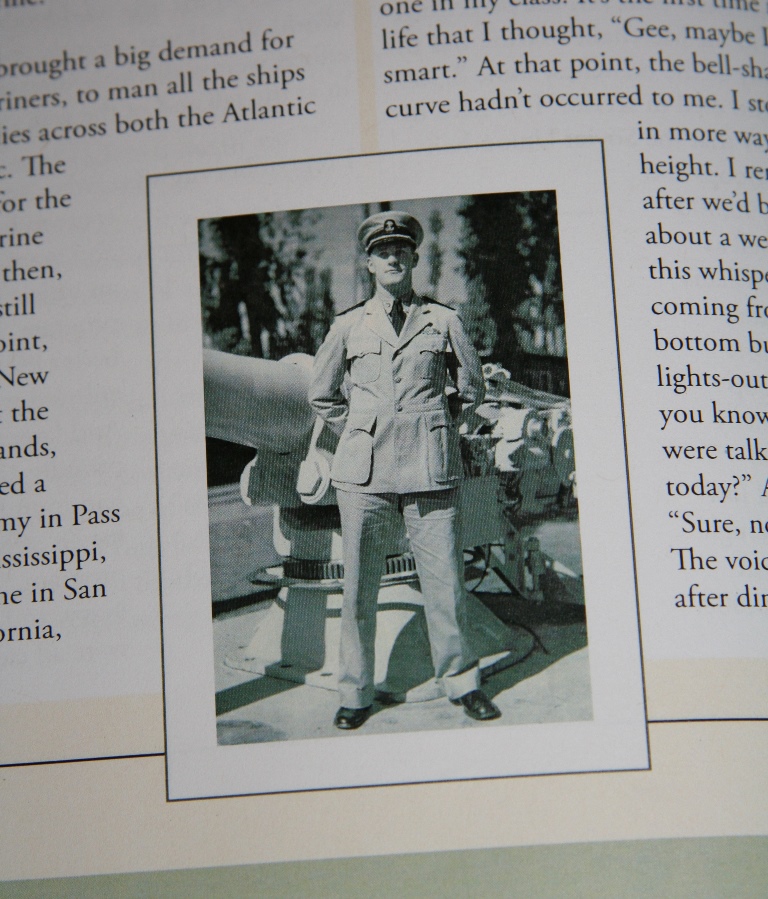

On June 8, 1945, after four-plus months in the academy, Moose went to sea as a cadet midshipman (engine), receiving a monthly salary of $77.50, to continue his studies and to learn life afloat.

“The cadets were assigned one to a vessel, and because I was number one in my class, I supposedly got the best ship, the S.S. Cape John, one of the many ships of that large transatlantic and transpacific shipping line. The crew members on the ship were employed by the Grace Line, a premier prewar passenger and cargo line. I would guess that at least half of the crew were 4-F, but so patriotic they wanted to serve their country by going to sea. The other half were overage – too old to serve in the Army or Navy – so they went to sea. I was called ‘kid.’”

There were three categories of freighters during WWII: Liberty ships; Victory ships; and bulk carriers. The Cape John, and other ships he would serve on were Break Bulk freighters.

“During my time at sea, I was lucky to have duty on such ships,” Moose wrote. “My bulk carrier was a C2 design. These ships were 459 feet long with a 63-foot beam, had a draft of 25 feet and were about 6-8,000 tons. The ships steamed along at a maximum of 15.5 knots.

The speed came from 440 psi high pressure steam and sophisticated machinery using turbines as the power source, he wrote. The ship’s speed was a major factor in avoiding the impending torpedo, Moose said.

“The submerged German submarine could only go at 8 or 9 knots, our C2 ships could outrun them. As a consequence, we never steamed in convoys, and simply went from point to point. We delivered goods quickly, with an average time of about 15 days from U.S. ports to our South Pacific island destinations.”

Freighters of this class were used and especially developed for use in shallow water ports, Moose said. Because of the large, open storage areas below deck, skids of cargo could either be loaded down into the hull either from a dock or barges and in very shallow ports, or when unloading lifted overboard to barges or directly on the dock. He has numerous photographs of the variety of ships he served on, and one shows the complex mix of lines needed to load and unload cargo from ship to dock, dock to ship. “Our ship needed no help from other cranes,” Moose said.

Life aboard the ships

Moose basically served with seasoned seamen on the ship. They expected to stay at sea, and they expected him to stay, as well.

“The old pros wanted me to learn everything about the ship the right way so that I would be a good engineering officer,” Moose recalls. “In essence, my future career as an academy grad was imagined to be with the Grace Line, and the pros were evaluating me for a permanent postwar spot.”

The crew was divided into the “deck gang” and the “black gang,” the engineers being the black gang both because of the memories of coal-burning days and because diesel oil is black. The lives of these two groups were totally separate. Because he was an engine midshipman, he was associated with the black gang, about 13 men with titles of boiler, firemen, wiper and maintenance. The crew was 100% volunteers – mostly 4F and over age patriots, Moose said.

The engine room temperature in the South Pacific was often 120 degrees. There were about eight sets of stairs to run up and down, and they worked seven days a week, 24 hours a day, with three eight-hour shifts to which one officer and three crew members were assigned. That left 16 hours off, during which there was a lot of reading, card playing, drinking, horsing around, fishing, and for Moose, doing his class assignments from the academy. The Merchant Marine Academy had sent a pile of second-year workbooks with assignments, questionnaires and essays to work on.

The chief engineer thought the best duty for Moose as maintenance, which was supposed to be accomplished during daytime, but whenever there was a crisis, they were on duty 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“So my days were maintenance and my nights and off-duty time were study and assignments,” Moose said.

All the engineering officers were willing to help Moose and explain things. They would ask him questions about the steam engines or what to do in case of emergency. “How can the safety valve be bypassed?” These were the kinds of incidentals Moose was supposed to understand.

The ship also had a “Navy armed guard,” of eight to 10 men on board, and a three- or five-inch gun, one fore and one aft, and two machine guns on each side. These were meant to prevent a submarine from surfacing and sinking the ship by returning surface fire.

“It was a very egalitarian world,” Moose remembers. “Everyone had civilian titles, and there was no Navy-Army talk at all. There was no, ‘Yes, sir! No, sir!’ Everyone was called a ‘mate.’”

When they pulled up next to a similar Navy ship, also running C-1 cargoes as his ship did, they would have 150 to 200 crew members on board, whereas Moose’s ship had a crew of about 45.

“We talked about that, and it was clear that our small crew could accomplish what had to be done because it was made up mostly of seamen who knew what they were doing,” Moose said. “Also, the Navy wanted double crews as a safety factor in case the ship was hit in battle.”

Moose’s tour on the S.S. Cape John lasted through the war years until November 1945. His duty took him to the Pacific Islands, including Eniwetok, Saipan, and Guam. It wasn’t all work, he said, and he remembers watching dolphins play while racing the ship and crisscrossing across the bow almost scratching their back on the hull of the ship. They used to sit on the fantail and watch the phosphorescent wake from the propeller, a beautiful sight.

They ate well at sea. Officers were served their meals on china plates. Each meal’s menu was typed on Grace Line stationery (Moose saved a few menus and printed them in his book).

There was no shore leave in the South Pacific, he said, and even though they came back to the states to take on cargo, it was always a rush. With wartime urgency, they loaded 24/7.

Because their cargo consisted of 55-gallon drums of gasoline, kerosene and acetylene, their captain wanted them to get in, unload, and get our quickly. Being in port was the maximum danger point from air raids. There was often much yelling and waving of the officer in charge.

A close call at sea

A bunch of the crew members on the Cape John had been sunk once or twice or more, and they smoked four packs of cigarettes a day and were still jumpy, Moose said. Because they were always alone, running at 15 knots, there were always crew members looking around to see if there were any submarines.

“On one occasion, the skipper up on the deck threw the Engine Order Telegraph, sounding the bell in the engine room, ordering us to increase the steam and blow the safety valve; it was as if we took off on the racetrack,” Moose said. “Our big ship leapt ahead, shuddering and badly vibrating. We were going 18 knots, and a call came from the skipper that said, ‘send the kid up here.’ I did so, and someone said, ‘Moose, watch over there, and you’ll see the torpedo coming.’ All of the off-duty crew was leaning over the side watching a torpedo come past our stern. I then understood why the skipper had increased speed. Our holds were full of 55-gallon drums of gasoline, kerosene, and acetylene – we were a floating bomb. That was my wartime thrill!”

Moose was in San Francisco on V-J Day. He went to Chinatown and the locals were really celebrating; the firecrackers were like confetti. He walked onto Market Street and everybody was hugging, happy and dancing. In the day’s excitement, he missed his ship’s sailing.

He eventually caught up with it. His wartime experiences were now over, but his sea duty was not.

Continuing postwar duty in the Merchant Marine

After V-J Day on Aug. 15, 1945, he was still a student of the U.S. Merchant Marine in his junior year and still on the Spitfire as a midshipman and as Coast Guardsman (where he remained from Feb. 22 to May 13, 1946). Before he resigned from the academy with an honorable discharge due to Meniere’s disease, he would serve on two other Grace Line ships: the Santa Teresa and the S.S. Pure Oil, and have several more memorable experiences.

One trip took him to both New Zealand and Australia. While in Auckland and Wellington, New Zealand, the chief engineer told him to take a couple days ashore. He did, and he really enjoyed it. They also docked in Sydney, Australia. He saw the pink cliffs of Sydney, similar to the white cliffs of Dover in England, only pink in color.

He found himself in Guam in late November 1945 while assigned to the S.S. Santa Teresa. He spent only about two months on board that ship, and was reassigned in February 1946 to the S.S. Spitfire. All the ships were new ships and all part of the Grace Line. His tour on the Spitfire took him on three trips to Latin America.

In May 1946 he completed his training afloat and passed by submitting the third class workbooks that he completed at sea. He was promoted to Second Class Cadet Midshipman, discharged, and had a month’s leave before going to Kings Point to continue his studies. As his leave ended, he tendered his resignation from the Merchant Marine Academy for the stated reason that “Cadet Midshipman Dunne does not believe himself suited for life at sea.”

He sees that decision as prescient, because within a month he suffered a serious attack of labyrinthine Meniere syndrome, otherwise known as inner ear vertigo. His physician declared him unfit for military service. His resignation was accepted on July 11, 1946. Shortly afterward, he received his notice of honorable discharge.

“I had been eligible for the Pacific war zone bar medal for voyages made to Saipan, and several years later would receive a letter of ‘heartfelt thanks’ from President Harry S. Truman,” he wrote.

Moose finds it interesting that he was not then eligible for veterans’ benefits, including the G.I. Bill, because Merchant Marines did not qualify in spite of the disproportionate numbers lost during the war. It wasn’t until 1988 that Merchant Marines from WWII became eligible for veterans’ benefits after President Bill Clinton declared them “veterans,” he said.

In his book about his life, Moose wrote, “My experience in World War II was not a bloody one. What one did in the war was a total accident of one’s age. If you were two or three years older, you were an enlisted man. I had New Trier classmates and football teammates who were killed on every island in the Pacific, whether Tarawa or Iwo Jima, and those other names that are lost by now. But I was at the tail end of WWII, and in college, too. I had grown up in an Irish enclave, had gone to the Irish church and was an Irish American. What did the war do for those my age who survived? It took each one of us kids out of wherever home was and gave us not only a geographical trip – California, New Zealand, Australia, Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, Chile – but also an opportunity to meet people from all over, including those in the Merchant Marine, whom I would never see again. In so doing, I lost my innocence and grew up.”

“After WWII I spent my life in public service, serving America with my God given blessings of time (now in my 90th year), talent (my mind still works) treasure (65 summers in Harbor Springs; six months of the year, six months in Clearwater, Florida),” he said.

Early years in Chicago

Born on November 30, 1926 in Chicago, Moose entered a family with a legendary lineage before he was born. His great-grandfather, Patrick William Dunne, was born in Ireland in 1832. He immigrated to the United States in 1849, following the revolution of 1848, at the age of 16. He settled in Watertown, Connecticut, married and had four children, before moving his family to Peoria, Illinois. One of their sons, Edward Fitzsimmons Dunne, (Moose’s grandfather) attended Union College of Law, graduated in 1877, and began a law practice. He married Elizabeth Kelly and together they had 13 children. His grandfather, Edward, became mayor of Chicago, and then Governor of Illinois. Under his leadership, Illinois became one of the first states east of the Mississippi River to grant women any voting rights with a bill that started the stampede to have a federal bill.

One of the Governor’s 13 children would be Moose’s father, Maurice F. Dunne, born 1895.

Moose’s father went to the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor to break away from the family heritage and high expectations everyone in Illinois had for members of his family. That decision started the Dunne family’s transition from Chicago to Michigan that continues today. His father, brother and four uncles sought their educations at the University of Michigan as well.

After he finished grammar school, Moose’s family moved from Chicago to Winnetka, Illinois, 17 miles north of Chicago. He had three siblings: two sisters; Elizabeth (Betty), and Janet; and a younger brother, Arthur, who served in Korea and became a judge. Moose has outlived all of them.

Maurice got the name “Moose” while attending summer camp in Ludington, Michigan. While playing baseball he ran back in the woods to catch the ball, fell, but caught the ball. The camp director said, “Now the campers know what a moose sounds like crashing through the woods.” He’s been known as Moose ever since. He embraced the name and his home is decorated with symbols of the noble creature.

Moose graduated from New Trier High School in 1944. At 17, he entered MIT and transferred to the University of Michigan where he played varsity football, then the war. After the war, he went to school at Northwestern University in Illinois to study engineering. He was there from 1946 to 1949. He went to work at the Pyott Foundry from 1943 to 1952, graduating from Northwestern while working at the foundry. He took a trip to Europe, studied business at Harvard for two years, and then met Eleanor “Ellie” Dennehy Isham. He married Ellie when he was 30 in 1957. They had three children and were married 50 years when Moose wrote his book 10 years ago. She passed away in 2008.

His education and career reads like a who’s who and a travelogue of the United States. He has his undergraduate degree from Northwestern; a master’s degree in Business from Harvard; and a second Masters degree in arts from Northwestern. Over the years he worked in the advertising industry and traveled quite a bit. He and Ellie were investors in an ice skating business. He was an Executive Vice President at both the Daily News and Tribune News in LaSalle, Illinois, and spent time in management in radio in Waco, Texas. Through it all, he was deeply involved in education both in engineering and business administration. In the 1950s, he was a faculty member at the University of Chicago. From 1957 to 1992, he was a faculty member at Lake Forest College. And he even owned a race horse at one time.

“The highlight of my post-veteran public service academic career was achieving full graduate degree accreditation for the Lake Forest Graduate School of Management (LFGSM) in north suburban Chicago, Lake Forest, from the North Central region Association of Colleges and Universities,” Moose said.

LFGSM was unique, he claims, because it was the only school in the entire 20-state region that was accredited, free-standing (not affiliated with a college or university), and where 100% of the students attended school part-time and were employed full-time, and the average age was 35 years old.

“The mission was enabling students to advance in their organizations,” Moose said.

With Moose as the first president, on Oct. 15, 1965, the LFGSM was incorporated as a not-for-profit. On March 9, 1973, the State of Illinois Board of Higher Education granted graduate degree certification to the school. On May 25, 1978, the LFGSM received full accreditation at the graduate level for the MBA degrees by the North Central Association of Higher Education. Moose retired from LFGSM in 1992 after 35 years of service was awarded President Emeritus status.

He was a trustee at Barat College and Walsh College, both in Troy, Michigan; and a trustee for the Center for Medieval Renaissance Studies at Oxford in England. He was Director and Chief Operations Officer for Northern Illinois Business Association in Chicago. For 13 years he was a Director at Lake Forest Bank and Trust, and over the yeas served on board of other banks. He was the Treasurer at the Little Harbor Club in Harbor Springs from 1996 to 2007. Moose has not spent life on the sidelines.

Moose and Ellie had three children: Ralph; Maurice, III, (Meath); and Tara. They raised their children in Lake Forest, Illinois, and spent their summers in Wequetonsing, in Harbor Springs. Ellie had discovered Harbor Springs years ago when she accompanied a girlfriend whose family had a cottage in the small, lakeside community. The Dunne’s bought a small cottage in Wequetonsing and built onto it in 1988. It now comfortably accommodates three families, and he calls it a “multi-generational cottage.”

Moose and Ellie began spending their winters in Clearwater, Florida, after he retired at 75 years of age. He now spends his summers in Wequetonsing and his winters in Florida, near the water year round. The family calls the northern Michigan cottage, “Dun Gone North,” and the Florida residence, “Dun Gone South.”

Moose is quite proud of his children and boasts of their accomplishments. Ralph became a policeman and earned his MBA; he lives in Tampa, Florida. Meath went to West Point’s Airborne School and served in the Army for 10 years. He’s married with two children and lives in Wellesley, Massachusetts. Tara, his daughter, graduated from Columbia University in New York, is married to Keith Stocker and lives in Chicago.

Moose keeps busy these days by attending educational programs and speakers and worship services at the Bay View Association, where he is an Associate member. He is a member of the Holy Childhood Catholic Church in Harbor Springs, and a member of the Rotary Club in Petoskey. He attends a men’s coffee group and lunch group where invigorating discussions ensue.

He summarizes his life as a “a lifelong commitment to public service and private organizations, including being employed for 78 years; 38 years as an adjunct for three graduate schools of management. While president of LFGSM, he also served simultaneously a total of 60 years as a trustee at three high schools and five colleges; and 29 years as a trustee on three corporate Board of Directors. All of these commitments overlapped with 56 years as an organization chairman for a total of 256 busy years of public service.

“Life is so good,” he often says. “God has granted me 90 years of faith, a healthy life and a mind still functioning,” Moose said.

Moose makes himself available for presentations to service clubs and other groups on his WWII and Veteran Day Honor Flight experience on Oct. 13, 2015, to view WWII memorials in Washington, D.C.

“If I can be of service, if I can do this, I’m happy to,” he said.

Web editor’s note: On a regular basis, Emmet County features the story of a local veteran to honor their service to the United States. If you have an idea for a person to feature — young, old, retired, currently serving, male or female – please contact Beth Anne Eckerle at beckerle@emmetcounty.org or call (231) 348-1704.