WWII vet a witness to history

Update: Hugh Winnell passed away on Aug. 9, 2012, at the age of 88. Emmet County sends its respects to Mr. Winnell and his family.

By Beth Anne Piehl

Hugh Winnell says he’s had two lives: The one he had before World War II, and the one he’s lived afterward, for the last 66 years.

Hugh Winnell says he’s had two lives: The one he had before World War II, and the one he’s lived afterward, for the last 66 years.

The 87-year-old Petoskey resident still vividly recalls in equal parts his exuberant youthful days at Petoskey High School and the intense, life-changing years as a fighter/dive bomb pilot during World War II.

“I think quite a few of us veterans feel like we have two lives,” said Winnell, 87, and a lifelong Petoskey resident who lives on the land near downtown that was originally his family’s farm. “The war is the pivotal part of your memory. I think of the war as maybe happening last week, it’s that vivid.”

Winnell is a reminder of that rare generation made up of kids who had barely turned their tassels before climbing aboard aircraft carriers and fighter jets, seemingly fearless in the face of the Japanese and Hitler in WWII. Their patriotic fervor led them from tiny communities like Petoskey onto the world stage; thousands wouldn’t return, though Winnell notes all of his classmates who enlisted upon their graduation in 1941 came home alive.

They enlisted just a few months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor.

“We were all enraged, and we were all anxious to get into the service and retaliate,” Winnell recalled. “My generation was far enough removed from World War I that we were not exposed to the carnage of that war.”

From playing ball in Petoskey to World War II

“Petoskey was pretty much isolated as a community back then,” recalled Winnell, who was born in 1924. “My dad came here as a barber in 1918, and railroads were big at that time.”

When news of the attack at Pearl Harbor reached Northern Michigan, Winnell and his classmates hustled to enlist in all branches of the military. Winnell enlisted in the Marine Corps in 1942, with the intention of becoming a pilot.

Winnell, aboard the Corsair fighter plane during WWII circa 1944.

He enrolled in the Navy’s V5 Program, an accelerated college education/pilot training course. For nearly a year and a half, he flew in Butte, Montana; he then attended boot camp in Oakland, Calif. and learned acrobatics in a two-wing biplane in Kansas.

In 1944, he earned his wings and became a second lieutenant, and his tour was about to begin. But before leaving for war, he returned to Michigan briefly to marry his high school sweetheart, Verajean. Verajean stayed in Petoskey and Winnell was sent to Corsair F4U training in El Toro, Calif. In January 1945, he was deployed with Squadron 222 of MAG-14, to the South Pacific.

From here, his story reads like an excerpt from high school history class.

After the Battle of Midway and the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Winnell and his team became dive bombers, blasting the Japanese on the ground around the Philippines with napalm, bombs and rockets. They would usually fly for 1 ½ hours to get to their target, spend 20 minutes on target, and return to base.

Their airstrip was a short coral reef that faced a steep mountainside on Samar Island, requiring pilots like Winnell to punch it upward – and fast. “It was just long enough for fighter planes, but then they added two, 500-pound bombs to our planes,” Winnell recalled, with a laugh. “It was challenging.”

Ground signals in the form of white smoke bombs from Army forces in the jungle would let the pilots know where to drop the bombs to maximize enemy casualties. And it was paramount to pay attention. “The Japanese were doing the same thing to try and throw us off target, so you always kept your eye on the first smoke bomb,” Winnell said.

Winnell recalled one particularly successful mission that took place at a mountain cave that had been dug out for railroad passage. The Japanese had set up a protected area inside, firing on U.S. troops and vehicles. Winnell’s squadron was called in to take them out. The problem: a steep mountain cliff ascending upward from the dug-out rail corridor.

The Marines rigged “skip bombs” into the bottoms of their planes by drilling a hole and wiring a release lever through the propeller and into the cockpit. Winnell and the 11 other planes flew overhead and released their bombs before pulling skyward at full throttle to scale the mountain face. “That was pretty exciting, to say the least,” Winnell laughed.

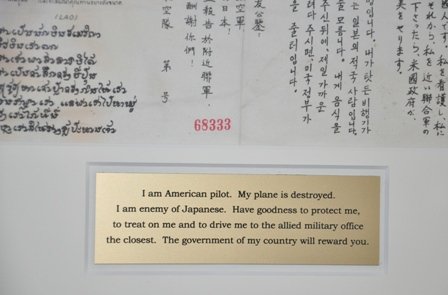

Winnell carried this cloth flag with him at all times, written in a number of different languages. He had

it translated several years ago by the owners of the Chinese buffet in Petoskey. It reads, “I am American pilot.

My plane is destroyed. I am enemy of Japanese. Have goodness to protect me, to treat on me and to drive

me to the allied military office the closest. The government of my country will reward you.”

Afterward, the Army invited Winnell’s squadron back, on the ground this time, to survey the results. “That was the closest I’d been to dead Japanese soldiers, and there were probably 20 of them,” Winnell said.

Toward the end of the war, Winnell shot down kamikaze planes attempting to hit U.S. aircraft carriers off the coast of Japan. In total, Winnell served as a dive-bomb pilot in both the Philippines (January-April 1945) and Okinawa (April-August 1945). During this time, the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He flew more than 40 missions, 23 of which he was fired upon. The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded to those who fly more than 24 missions under fire.

Still, his life and the lives of his comrades were always on the line.

“We lost some friends, but when you’re 19 and 20 years old, you have this belief that you’ll live forever,” Winnell said, in a newspaper interview on Veterans Day 2010. “You’re at the height of your physical ability and you have this airplane that goes 400 miles per hour. You have this aura of invincibility … it’s not going to be me.”

After returning to the U.S. via Portland, Oregon, Winnell made his way back to his bride, in time for Christmas 1945. They had two children together before Verajean died in 1952 of kidney failure. That year, Winnell was about to be called back as a fighter pilot for the Korean War, but he was instructed instead to stay home and care for their two young children, just 4 and 5 years old. He was discharged from the Marines as a Captain after serving with his unit VMF 222.

A commemorative stamp of the Corsair, the plane Winnell flew in WWII, was issued by the U.S.

Post Office a few years ago. Winnell has this enlarged version framed in his living room.

His life back in Petoskey returned to the pace it did before the war. He worked for 25 years as a barber at the Palace Barbershop in downtown Petoskey, and then worked for Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance.

But he has never forgotten the sacrifices of so many, and his own tours of duty serving the United States.

“You don’t know why you were spared, but that’s the way it happens,” said Winnell. “I never spoke a whole lot about my experiences in the war for quite some time, because you felt you were lucky to be home. I lost some good friends.”